Valkyrie Savage, UC Berkeley

Björn Hartmann, UC Berkeley

Tangible user interfaces (TUIs) are, according to Hiroshi Ishii, about “mak[ing] digital information directly manipulatable with our hands and perceptible through our peripheral senses through its physical embodiment”. Although touch screen-based interactions are increasingly popular as smartphones continue to sell, there are still strong arguments for maintaining the tangibility of interfaces: these arguments range from speed and accuracy (a gamer using a gaming console) to visibility (ability of others to learn and interact with one’s data in a shared space) to safety and accessibility (including eyes-free interfaces for driving). We have previously investigated the benefits of tangibility in How Bodies Matter.

3D printing holds obvious promise for the physical design and fabrication of tangible interfaces. However, becasue such interfaces are interactive, they require an integration of physical form and electronics. Few of the early users of 3D printing can currently create such objects. For example, we surveyed the the online community Thingiverse; presently it and sites similar to it show a definite tilt towards objects like 3D scans of artwork at the Art Institute of Chicago. These things are immobile, captured rather than designed, and intended to be used as jewelry or art pieces. A smaller set of things on the site have mechanical movement of some kind, like toy cars and moon rovers. A third, yet smaller, class are things that are both mechanically and electronically functional, like Atari joystick replacements. The users who dabble in this last sector are typically experts in PCB design and design for 3D printing.

|

|

|

| “Iconic Lion at the Steps of the Art Institute of Chicago” by ArtInstituteChicago on Thingiverse | “Moon Rover” by emmett on Thingiverse | “Arcade Stick” by srepmub on Thingiverse |

Many of the objects on Thingiverse focus on 3D printable designs. Aside from 3D printers, other classes of digital fabrication hardware, like vinyl cutters, have also reached consumer-friendly price points. Our group at Berkeley is examining how to combine the capabilities of these types of hardware to assist designers in prototyping tangible input devices, with an eye towards the ultimate goal of making hardware prototypes more like software prototypes: rapidly iterable and immediately functional through tools that are easily learned. We want to use our work to educate and excite high school students in STEM fields.

Our first project, Midas, explored the creation of custom capacitive touch sensors that can be designed and made functional without knowledge of electronics or programming skill. These types of sensors can be used, for example, to enable back-of-phone interactions that don’t occlude output while a user gives input; or to experiment with the placement of interactive areas on a new computer peripheral. We even used it to build a touch-sensitive postcard that plays songs and a papercraft pinball machine that can actually control a PC-based pinball game.

The Midas video submitted to UIST 2012, describing the user flow and basic implementation of the system, can be found on YouTube.

|

| A Midas-powered prototype enabling back-of-phone interactions for checking email. |

Midas consists of a design tool for layout of the sensors, a vinyl cutter for fabrication of them, and a small microcontroller for communication with them. The design tool takes the drag-and-drop paradigm currently prevalent in GUI development and expands it to hardware development: the designer does not trouble herself with the “plumbing” that turns a high-level design into a lower-level representation for display or fabrication. In a GUI editor this means the tool is responsible for determining pixel locations and managing components at runtime, while in Midas we create vector graphics of the designer’s sensors and appropriate connective traces. In both cases, the designer is free to concern herself with the what rather than the how. Once a designer has completed her sensor layout with Midas, instructions are generated which lead her through a multi-step fabrication and assembly process. In this process, she cuts her custom sensors from copper foil on a vinyl cutter, adheres them to her object, and connects them to color-coded wires. She then uses the interface to describe on-screen interactions through a record and replay framework, or to program more complex interactions through WebSockets.

In user tests, we found the tool suitable for first-time users, and we found interest in it at venues like FabLearn, a conference for fabrication technologies in education; and Sketching in Hardware, a weekend workshop for hackers, artists, and academics. However, it has a fundamental limitation: it only assists designers with touch-based interactions. In the larger TUI world, there are many more classes of input to be considered.

|

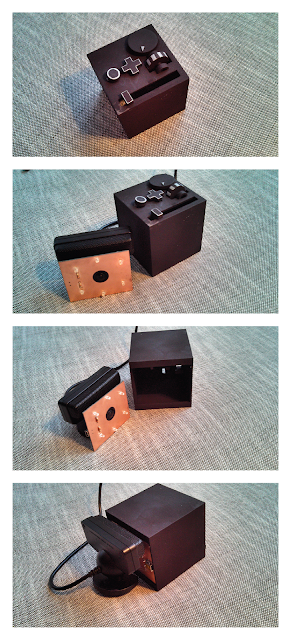

| A Sauron-powered prototype of a controller with a button, a direction pad, a scroll wheel, a dial, and a slider. |

Continuing our explorations, we have begun a project to enable designers to turn models fabricated on commodity 3D printers into interactive prototypes with a minimum of required assembly or instrumentation. We share a goal with Disney’s work: functional tangible input devices which can be fabricated on a 3D printer without intensive post-print assembly. Our approach involves inserting a single camera into a completed input device print. Our current prototype, Sauron, consists of an infrared camera with an array of IR LEDs, which can be placed inside already-printed devices. The camera observes the backside of the end-user-facing input components (e.g. buttons, sliders, or direction pads), and via computer vision determines when a mechanism was actuated and how (e.g. it can give the position the slider was moved to along its track).

This allows designers to create functional objects as fast as they can print them: the only assembly required to make the parts work with Sauron is to insert the camera. Our next steps in this project include developing a CAD tool plugin that will aid designers in building prototypes where all input components are visible to the single camera; the plugin will automatically place and move mirrors and internal geometry to make all components visible within the cone of vision. This again frees the designer to think about the what rather than the how as prototypes come out of a 3D printer essentially already functional.

The world is interactive, but most things created using digital fabrication aren’t yet. Through our work at Berkeley, and hopefully our interactions with the FAB at CHI workshop, we are hoping to explore the potential of digital fabrication tools for functional prototype design.